The recent waning of the founder-CEO premium… but why I’m still bullish in the long-run

Historically, founder-led companies tend to outperform non-founder led ones. But this gap has recently converged. I discuss what may be driving this & why I believe the founder-CEO premium will return

A few weeks ago, I was approached by a reporter at The Economist to offer perspective on the shrinking “founder-CEO premium” in public markets. Comparing founder-led and non-founder led businesses within the BVP Nasdaq Emerging Cloud Index (EMCLOUD), The Economist observed that market capitalization (note that I consider this to be a proxy since this metric is a derivation and not a purist measure of returns) of founder-led companies had consistently outperformed the rest of the cohort from 2018 until the end of 2021, but this gap essentially converged since the SaaSacre in early 2022:

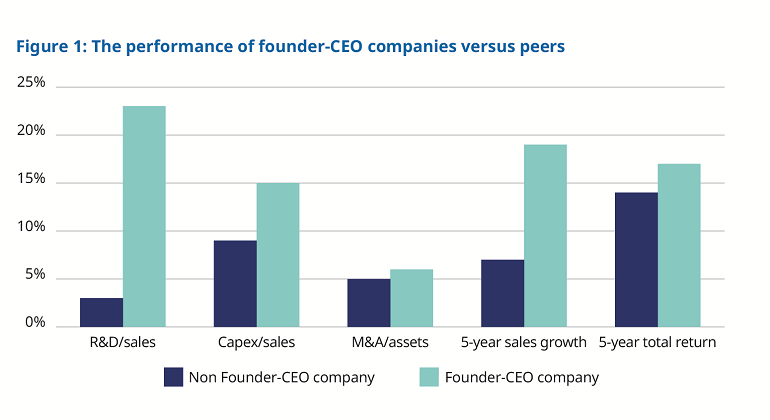

This observation is notable since there has been a considerable amount of data over the years supporting the theory that companies with founder CEOs tend to outperform the market and/or peers with non-founder CEOs as an investment class:

A 2005 Harvard Business Review article reported that founder-led companies had a market-adjusted return of 12% over the course of three years and a survival rate of 73%, compared with a return of -26% and a survival rate of 60% for companies that hired a professional CEO and moved the founder to a different position on the management team.

A 2009 study published in the Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis concluded that an equal-weighted investment strategy that had invested in founder-CEO firms from 1993-2002 would have returned 4.4% annually in excess of the market.

A 2010 study published in the Journal of Risk Financial and Management found that irrespective of market capitalization and time period, founder-led public companies significantly beat benchmarks from 1998 to 2010 across equity performance as well as several risk return metrics including rate of return, alpha, Sharpe ratio, Sortino ratio, informational ratio, and up-market capture ratio.

A 2010 University of Pennsylvania study focused on recently-IPOed SaaS companies discovered that founder-CEOs consistently outperformed professional CEOs on metrics such as capital efficiency, time to exit, exit valuation, value created, and return on investment.

A 2016 Harvard Business Review article documented a study from Bain and Company showing that founder-led businesses within the S&P 500 performed 3.1x better than the rest in terms of indexed total shareholder return during the 1990 to 2014 period:

As a venture capitalist who invests in early and growth-stage startups, it should come as no surprise that I inherently believe in the power of founder magic and entrepreneurial mentality. A significant majority of the investments I’ve made have been in startups led by a founder-CEO. In fact, the founder or founding team is almost always a key consideration within my investment thesis when searching for category-creating potential in the early days of a business. Since there has been so much published literature on this topic, the purpose of this post is not to deep dive into why it is advantageous to have a founder-CEO at the helm. Rather, I’d like to present two working hypotheses on the drivers of The Economist’s recent observation in convergence, especially within growth-oriented cohorts such as the EMCLOUD.

Hypothesis 1: Market paradigm shift favoring profitable growth

One explanation is that with the market paradigm shift at the start of 2022, investors have increasingly prized profitable growth over growth at-all-costs, and this evolution may play into a different skillset from a founder’s typical core superpowers.

Founders often start as specialists with skill spikes in particular areas such as product, engineering, or go-to-market, before growing into a more general management CEO role. These spikes are coupled with a clear founding vision of where they want to take their company. This founder magic tends to be an advantage when driving growth, since founders often possess deep product knowledge, differentiated instincts about the market and competitive landscape, and have the courage to take risks to implement new ideas or expand into new areas to achieve their unique vision.

In many cases, the leadership traits and mindset that fuel the drive toward growth differ from those that drive profitability, since the latter involves more managerial optimization skills around operations and finding efficiencies up and down the P&L, which aren’t necessarily the initial strengths of a founder. As Ben Horowitz wrote in 2010, “founding CEOs are excellent at finding, but not maximizing, product cycles” while “professional CEOs are effective at maximizing, but not finding, product cycles.” In fact, a meta-analysis of 117 studies across 22 countries conducted between 1987 and 2020 concluded that founder-CEOs experience performance advantages over professional CEOs in high discretionary institutional settings.

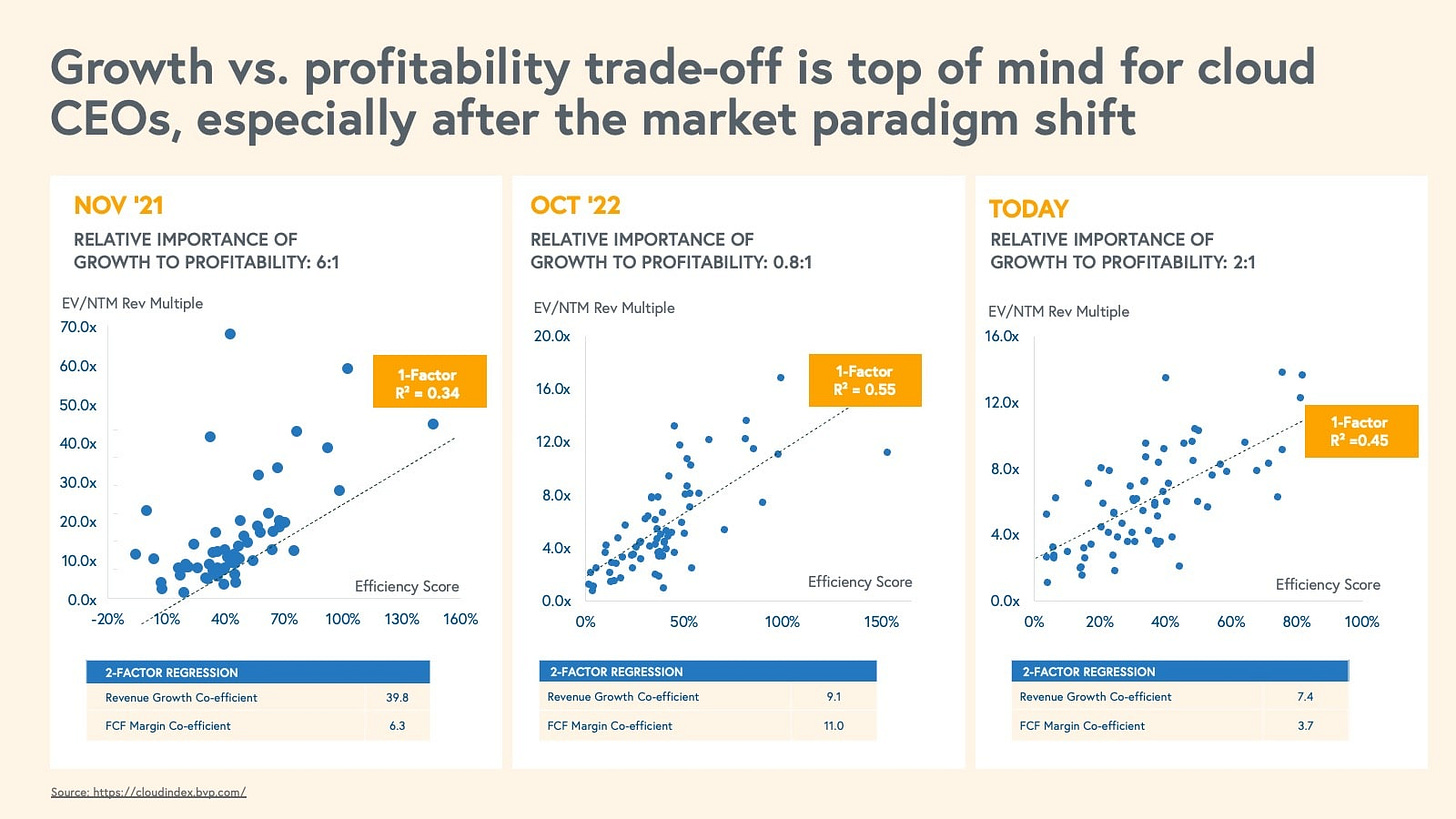

In the hype of the 2020-2021 period, cloud markets were prioritizing growth over profitability. As I covered in Bessemer’s State of the Cloud 2023, at the height of bull market exuberance in 2021, an incremental increase in growth was more impactful to valuations than an incremental increase in profitability by a factor of 6:1. It was thus not particularly surprising to observe a peak founder-CEO premium during that period since investors heavily rewarded growth.

However, as we know, the tide turned in 2022, and by late 2022, this ratio moved closer to ~1:1 and even tipped slightly in favor of profitability (chart above). When comparing the two groups, The Economist observed that founder-led businesses within EMCLOUD have been able to drive higher absolute revenue growth, while non-founder led business have been able to drive a higher level of FCF in recent years (chart below). This lens could help to explain the recent trend in convergence.

Hypothesis 2: Short-termism

Another theory is that during uncertain times such as these, markets tend to focus on the short-term which applies greater pressure on leaders to deliver immediate results. And in this case, immediate results around profitability. While developing innovations can take years, the quarterly results reporting cadence draws constant scrutiny to short-term earnings. Failing to meet analysts’ expectations each quarter has led in some instances to significant shifts in share price, immediate impact to a professional CEO’s bonus incentives, and even the removal of the CEO. This could cause non-founder CEOs to manage to short-term earnings to meet the market’s expectations, such as delaying long-term investments by cutting R&D expenses or holding off on M&A.

But the risk-reward decision framework for founders who started a company from scratch is very different from that of a professional executive who has been handed a company to manage, and also vastly different from that of investors. The opportunity cost for founders is always higher given they do not have the benefit of diversification — from a portfolio theory perspective, the minimum required return for founders tends to mirror that of an undiversified investor (where the Sharpe ratio of the new opportunity has to exceed the Sharpe ratio of the old opportunity before an investment decision makes sense) versus diversified investors have minimum required returns that follow the Portfolio Improvement Rule or the Capital Asset Pricing Model.

Thus, founders tend to be less myopic, and often take a long-term view given they already have significant ownership in a business, higher opportunity cost, and oftentimes a special attachment to their company akin to a parent-child relationship. All of these factors fuel the drive to ensure a lasting legacy for the company they built. Founders tend to be more willing to make long-term and risky investments in areas such as M&A, long-term capex initiatives, employee programs, and innovation projects (explaining the R&D spending trend from The Economist’s chart in the previous section) which may take years to produce results (chart below). Founders are less concerned about hitting the market’s expectations on a quarterly basis and are less influenced by short-term disruptions to stock price since they know they are taking steps to build an enduring business.

One study even noted that founder-CEOs are correlated with a 31% increase in patent counts before controlling for R&D spending, and a 23% increase in patent counts after controlling for R&D spending. And this trend seems to be global: an empirical study of China’s GEM-listed companies observed that founder CEO firms have a higher innovation output compared to non-founder CEO firms. This is why I’m still bullish that over time, we’ll revert to the historical trend and see the founder-CEO premium persist, especially within verticals such as the technology and cloud industries where an emphasis on innovation is a key driver of competitive advantage.

As we witness an increasing number of founder-CEO resignations (such as that of Whitney Wolfe Herd from Bumble and Kyle Voight from Cruise just within the past few weeks) as well as shocking founder-CEO firings (such as Sam Altman’s dramatic ousting from OpenAI) in recent months, I suspect that we’ll continue to revisit this topic of founder-CEO vs professional-CEO performance within the growth-stage tech world for many years to come.