Unraveling stock-based compensation overhang in the SaaS industry (Part 1)

SBC is a hot-button issue in the cloud world today. Part 1 of this series covers a discussion on: overreliance on SBC as an incentive tool and SBC as a smoke-screen to “flatter” financials.

SBC is such a meaty topic that I had to turn this into a 2-Part Series. Part 1 covers A) Overreliance on SBC as an incentive tool and B) SBC as a smoke-screen to “flatter” financials.

It’s been called everything from “the disappearing expense”, to “the greatest trick Silicon Valley ever pulled”, to a “damned lie”. Legendary investors such as Warren Buffett have weighed in with impassioned responses. Many public cloud companies addressed this issue in recent earnings calls.

Yes, we’re talking about stock-based compensation (SBC), a long-debated and controversial topic in the tech world. This subject has reared back into focus today following the recent market pullback which brought renewed scrutiny on long-term profitability, as well as a growing acknowledgement of SBC overhang within the software industry — SBC as a % of revenue for EMCLOUD companies averaged 21% in latest FY vs. 2% for S&P 500 companies.

Point-in-time SBC as a % of revenue is certainly not a perfect way to measure SBC magnitude since it could be distorted by events such as M&A or IPOs. But directionally, even after attempting to adjust for such events, the median SBC as a % of revenue in the software universe tends to fall within double digits, with some companies even going above 50% (visual above). Another lens to assess SBC impact is from a dilution perspective which has also exploded just within the last few years:

While it makes sense that high-growth companies (including many SaaS companies) are leveraging SBC more than mature counterparts, one would expect that such companies should be depending less on SBC as they move through their growth cycle and become more cash-generative. However, this has not been the case. Even for large cap SaaS companies, SBC is growing faster than revenue at 1.1x vs. 0.9x for S&P 500 companies. Another representation of this trend is that SBC as a % of revenue in the last 12 months vs 2 years prior has not decreased much for many SaaS companies:

As the cloud community comes to terms with SBC overreach within the industry, there have been heated and diverse reactions from various stakeholders, even on seemingly first-principle questions such as how to measure and control SBC impact. In this 2-Part Series, I dig into key debates over the controversies and risks of SBC overhang from a software investor's perspective:

A. Overreliance on SBC as an incentive tool

B. SBC as a smoke-screen to “flatter” financials

C. Valuation implications of SBC

D. Managing SBC impact

A. Overreliance on SBC as an incentive tool

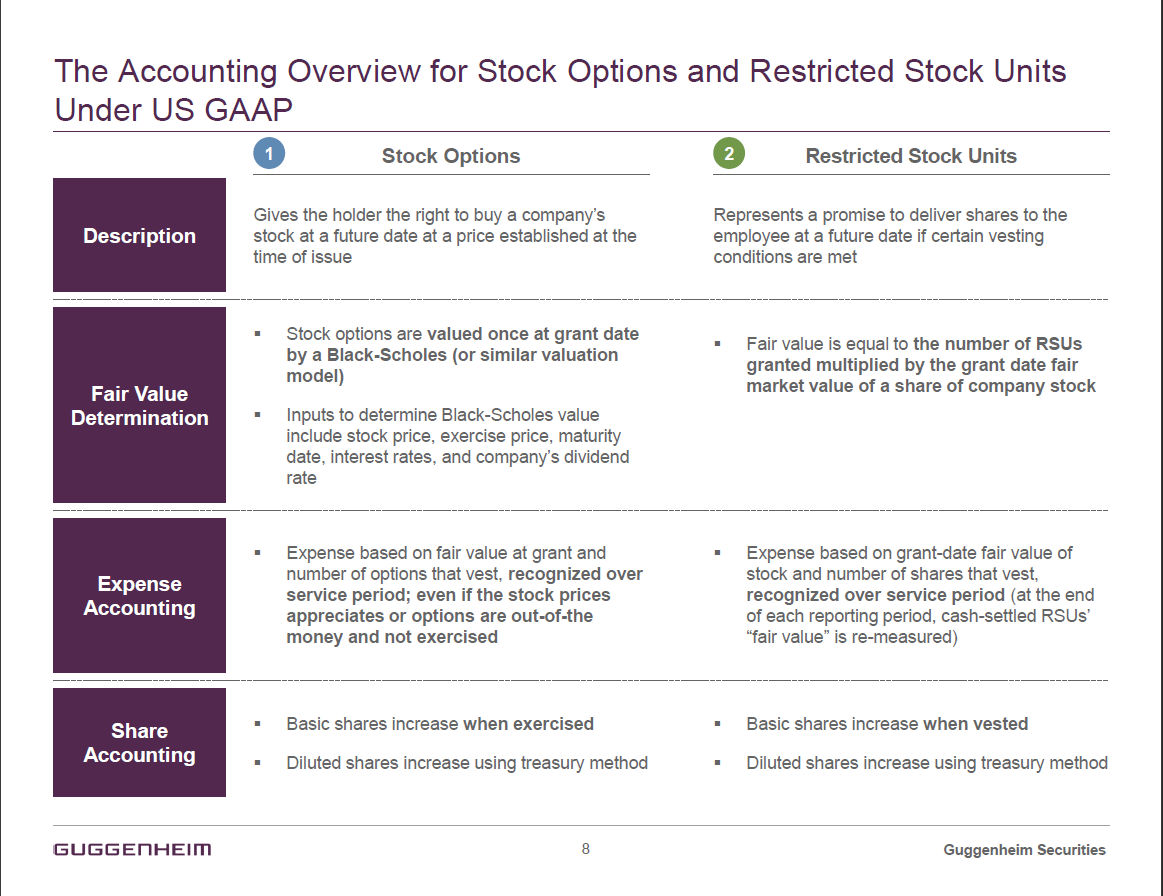

SBC is a non-cash form of compensation that pays employees, executives, or directors, of a company with equity in the business. The most common forms are:

Stock options which gives the holder the right to buy a company’s stock at a future date at a price established at the time of issue, and

Restricted stock units (RSUs) that represents a promise to deliver shares to the employee at a future date if certain conditions are met.

SBC can offer meaningful human capital benefits when used effectively, such as:

Retention: When paired with a vesting schedule or used as a performance reward, SBC can help to retain existing employees. A 2017 Study from the University of Pennsylvania found that overall benefit-cost ratios ranged from 1.95-3.75.

Hiring: SBC can be an attractive recruiting tool, especially for high-growth companies where there could be a perception of significant upside potential to the company’s stock.

Incentive alignment: Following principal-agent theory, SBC could help align incentives since employees, especially senior executives who may be paid heavily in stock, have ownership in the company.

Cash conservation: Growing companies that are cash consumptive and need to be mindful of burn can leverage SBC to remain competitive in the race for talent and still offer market rate compensation by shifting cash pay to stock.

Considering all these benefits, SBC tends to be adopted to a greater extent by high-growth companies that are still maturing through their growth S-curve:

But questions have been raised about the underlying merits of leveraging SBC as a human resource incentive tool. For instance, studies have found that CEOs with a lot of stock options demonstrated more risk-seeking behavior that was not always beneficial to the company, and in some sinister cases, even exhibited illegal conduct. RSUs are not devoid of criticism either; Bill Gurley of Benchmark asserts that 95% of RSUs are sold on vest which defeats the purpose of giving employees skin in the game.

My view is that SBC is not inherently good or bad, but can become problematic when overused. SBC overreliance can start to backfire during less robust market environments, especially when there is a sharp decline in a company’s share price. Retention can become challenging when options are meaningfully underwater or when the value of the RSUs are significantly lower than what employees had initially expected. When faced with this conundrum, companies could react in different ways but each have undesirable consequences:

Issue more SBC but this would cause more dilution. Several public cloud companies have done this and received pressure on their share price (more on this in Section C). This becomes a negative feedback loop as again a company would require greater issuance to achieve the same level of employee compensation.

Non cash-strapped companies could shift more compensation to cash but this could put pressure on previously-reported margins.

Companies that are more reliant on options could consider repricing but there are a slew of considerations and restrictions which make this challenging.

Do nothing and risk employee turnover.

This spiral of risk from overreliance on SBC may not be fully appreciated by stakeholders who have been accustomed to bull-market conditions. Private cloud startups have additional considerations such as illiquidity, and even less flexibility in their ability to take rectifying action when SBC concerns begin to compound. Ultimately, the most unsettling concern is that employees (especially early employees who made significant company-building contributions) could be left holding the bag.

B. SBC as a smoke-screen to “flatter” financials

Since SBC involves the issuance of stock, it does not technically involve a cash outflow as no cash changes hands. This non-cash nature of SBC has complicated how to capture the economic cost of SBC and accurately account for such transactions in financial statements. This has been a heavily debated topic for many decades now, with accounting rules evolving over the years:

Pre-SFAS No. 123R

SBC started gaining popularity in the late 1980s. In 1995, the Federal Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issued SFAS No. 123 where companies were “encouraged” to expense the estimated fair value for the stock grants they issued, but were also given the option to disclose this value in a footnote. By 2000, a majority of companies were using the footnote approach rather than expensing. (I recommend reading this Harvard Business School case which comprehensively documents these events).

This period marked the height of debate around whether SBC, although non-cash in nature, should be considered an expense. Since SBC is a form of compensation and many companies eventually end up spending real cash to buy back shares in order to counter the dilutive effects of SBC (more on this in Section D of this series), omitting this cost on financial statements could be misleading. Warren Buffett addressed this issue with fervor multiple times:

“If options aren’t a form of compensation, what are they? If compensation isn’t an expense, what is it? And, if expenses shouldn’t go into the calculation of earnings, where in the world should they go?” - 1992 Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letter

“This Alice-in-Wonderland outcome occurs because existing accounting principles ignore the cost of stock options when earnings are being calculated, even though options are a huge and increasing expense at a great many corporations. In effect, accounting principles offer management a choice: Pay employees in one form and count the cost, or pay them in another form and ignore the cost.” - 1998 Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letter

Post-SFAS 123R

In late 2004, SFAS 123R (now ASC 718) was released, requiring that stock options be recorded as an expense. Under GAAP accounting, SBC is now expensed either in COGS or OpEx on the income statement. Furthermore, different types of SBC have specific methods for fair value determination and accounting recognition:

This new accounting requirement was controversial. Beyond the typical debate around whether SBC constitutes a “real” expense, questions were raised around whether the proposed valuation methods were an accurate representation of costs, and if new accounting standards were overly punitive due to “double-counting”:

“If expensing were … required, the impact of options would be counted twice in the earnings per share: first as a potential dilution of the earnings, by increasing the shares outstanding, and second as a charge against reported earnings. The result would be inaccurate and misleading earnings per share” - John Doerr & FedEx CEO Frederick Smith in New York Times column (April 5, 2002)

Today

In reaction to the new accounting standard, companies increasingly began reporting “adjusted”, non-GAAP metrics that excluded SBC. This opened up a can of worms. For instance, there are companies that report being profitable on a non-GAAP basis while being unprofitable on a GAAP basis due to SBC. Here is an interesting thread with different case studies:

One non-GAAP metric that has received a lot of attention in this debate is free-cash-flow (FCF), which is commonly calculated as (Earnings before interest and tax * (1 – tax rate)) + Depreciation & Amortization - Change in Net Working Capital - Capital Expenditures + Non-Cash Charges. Since SBC is a non-cash charge, it is added back when forecasting FCF which can result in SBC being “ignored” in a discounted-cash-flow valuation model. FCF is also an input into efficiency metrics that have been heavily evangelized in the realms of VC and growth equity, such as the Rule of 40.

As uncertainty continues in the markets, there has been a resurgence in the discussion around the accuracy of “non-GAAP” metrics in representing a business’ underlying long-term profitability profile. I still view FCF as an important KPI for cloud businesses— cash burn limits runway for businesses that are consuming capital and for businesses that are cash-generative, FCF represents re-investable dollars that funneled back into the business or returned to shareholders. However, I acknowledge that things can become hairy for companies that have extremely high-levels of SBC, and as we discussed earlier, software companies are a major ‘offender’ in this regard.

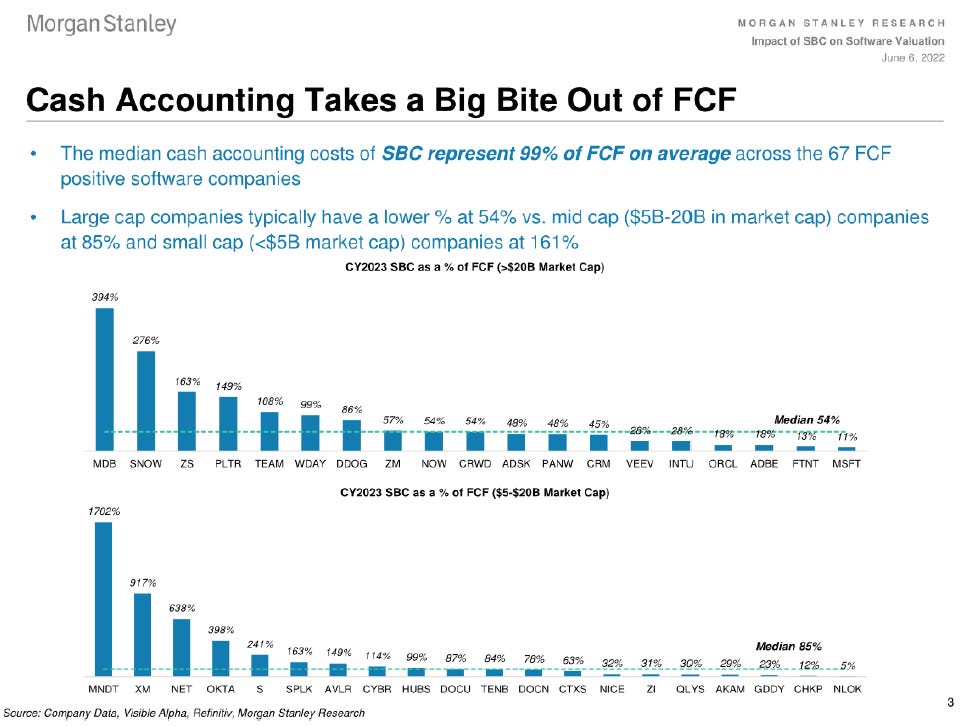

For instance, Wellington found that SBC represents a meaningful portion (39%) of current FCF for large cap SaaS vs. 4% for S&P 500 companies, and also flatters FCF margins to a more significant degree (12% vs. 1%). Additionally, there are SaaS companies where FCF margins look strong but SBC is more than 100% of FCF, which raises doubts about true profitability profile:

In fact, Morgan Stanley found that across 67 FCF positive software companies, median cash accounting costs of SBC represented 99% of FCF on average:

Given the pervasiveness of this issue in the SaaS world, we are currently in the eye of the storm of how FCF reporting could be improved to account for SBC impact:

Brad Gerstner of Altimeter suggests that “Unlevered FCF - SBC is the new EBITDA”.

RBC has proposed adjusting FCF margin for SBC using a conversion factor.

Gavin Baker of Atreides recommends a fully-loaded metric such as FCF per share.

In the next installment of this series, we’ll discuss dilution impact of SBC on valuation as well as mitigation responses from companies. Please subscribe to receive Part 2 when it goes live!

Great article Janelle, thank you for sharing.

Regardless of how you you include in the valuation, the dilution from SBC somehow it must be included (which even some Wall Street analysts didn’t). Under the same dilutive assumptions the valuation should not change.

I personally think the FCF per share focus is the best way because it preserves the idea that the company produces cash (net cash increases), yet that value is not fully captured by equity holders (https://palantirbullets.substack.com/p/why-99-of-palantir-dcfs-fail).

Looking forward for your second part!

Great article. It would be interesting to see augmented rule of 40 metrics with SBD and other adjustments added in for companies. Yours is the first industry comparison chart I have seen showing FCF before and after - shocking. I understand why companies don't when getting off the ground, but it becomes a crutch as they mature. Snowflake shocks me the most.