Consumption vs. subscription business models during downturns

Usage-based pricing has grown in popularity across the software stack. Consumption models are poised to capture outsized gains during expansionary periods, but what happens when the tide turns?

Over the past two decades, the progression towards cloud delivery has coincided with a tectonic shift in economic models for software businesses — from perpetual license format toward subscription models based on units such as seats or volume. In recent years, another evolution has been brewing, where consumption-based models are rising in prominence.

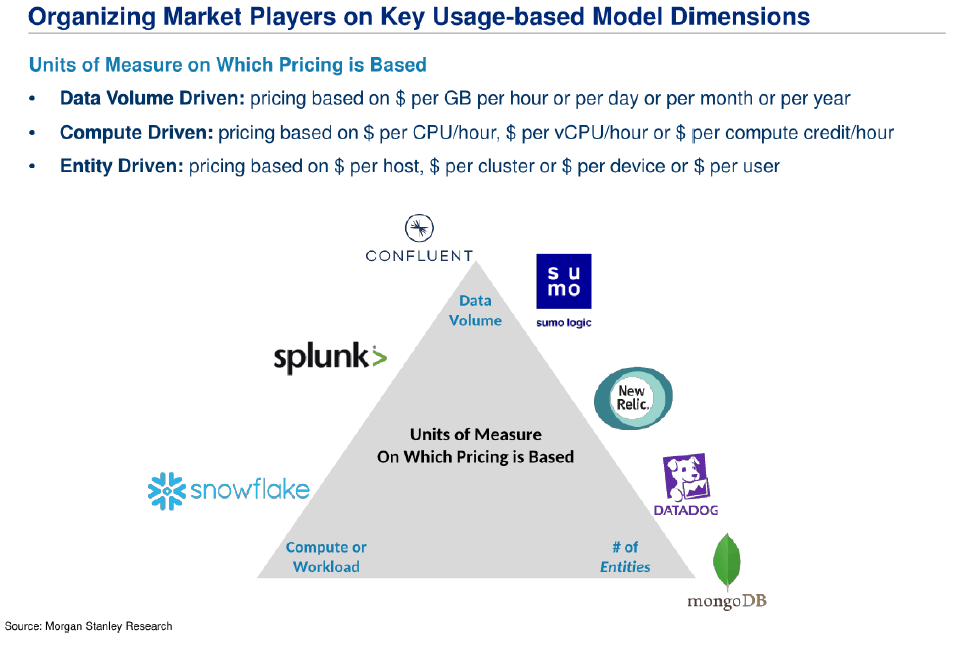

A key differentiator of consumption models is monetization based on metered usage (chart above). Such “pay-as-you-use” models have existed for a while now within the cloud universe, most notably within content delivery network platforms (such as Akamai and Edgio/Limelight) and cloud providers (such as AWS, Azure, and GCP). More recently though, consumption models have become increasingly popular amongst infrastructure and developer-oriented software companies, such as Confluent, Datadog, Digital Ocean, Elastic, Fastly, MongoDB, New Relic, Snowflake, and Twilio, within the BVP Cloud Index. This trend has also started to permeate into other layers of the software stack with application companies such as Autodesk introducing usage-based pricing options.

While the subscription model is still the more common archetype within the software realm, there are several various advantages of consumption-based models (see exhibit above) that make it highly attractive to particular business types. For instance, as my colleague Ethan Kurzweil and I noted previously, product-led growth companies may find usage-based pricing to be a strong accelerant for their go-to-market strategy.

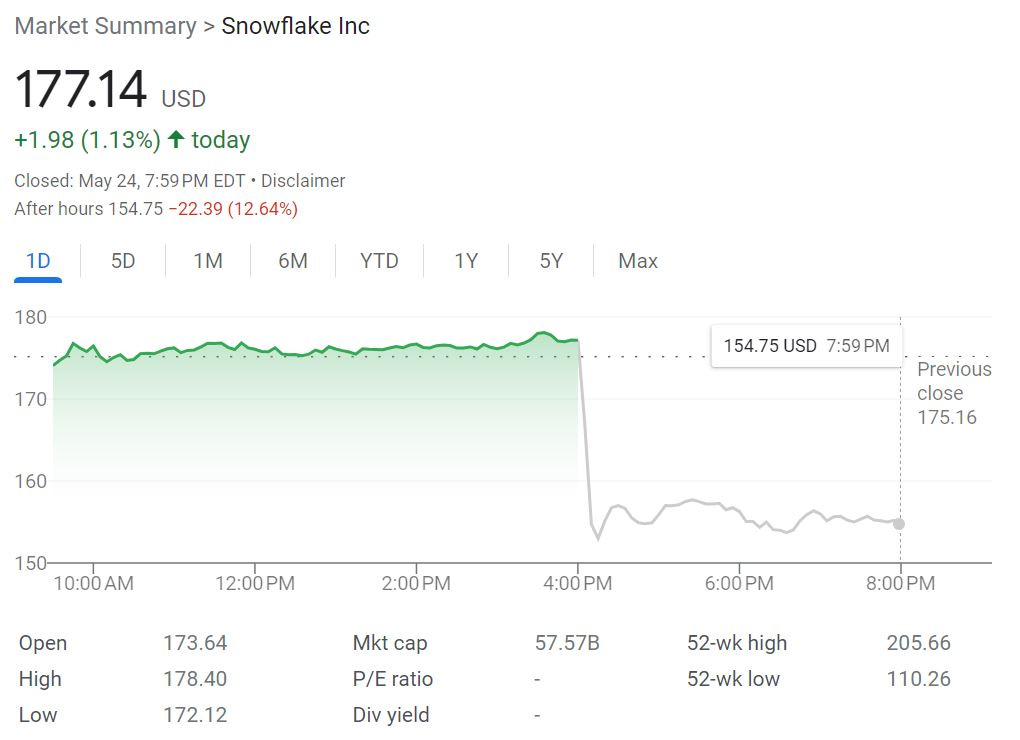

But the advantages of this model are not without trade-offs. Last week, cloud data infrastructure company Snowflake reported its FY24 Q1 earnings. While the company posted solid headline and bottom-line numbers that beat consensus expectations, it lowered FY24 revenue growth outlook for a second time within the last 2 quarters, causing the stock to tumble ~13% after hours (chart above). Snowflake pointed to degrading consumption patterns and a lack of predictability of when headwinds might subside as key reasons for the revision (solid recap from

on this), highlighting some of the vulnerabilities of usage-based models during weak macro environments. In this piece, I dig deeper into this topic by comparing the performance of consumption vs. subscription software models in the current downturn:Heightened sensitivity of consumption models to end-customer demand dynamics

Reduced visibility when predicting consumption patterns

Valuation implications for consumption models

I. Heightened sensitivity of consumption models to end-customer demand dynamics

One of the core tenets of the consumption model is that it aspires to align pricing closely with realized value since the customer only pays for what they use. This helps to reduce the potential for “shelf-ware” (i.e. unused capacity) leading to benefits such as happier customers and stronger retention dynamics. Additionally, in contrast to subscription models where customers typically wait till contracts come up for renewal to expand, consumption models make it easy for customers to expand intra-period, which reduces friction and sales effort in a land-and-expand motion. Indeed, Goldman Sachs found that consumption companies captured outsized revenue growth compared to the broader software group during the post-pandemic demand boom:

While consumption models are structurally poised to be considerable beneficiaries during expansionary periods, the reverse also holds true during recessionary periods, since customers can instantaneously cut back on usage to reduce spending during tough economic times. This impact will show up on earnings right away since revenue recognition in a consumption model is a function of usage and time. On the other hand, subscription models generally recognize revenue ratably, making such revenue more durable during downturns since demand impacts are spread out over time. For example, in a seat-based subscription model, the customer is generally still responsible for a certain number of pre-paid licenses during the contract period even if they end up reducing headcount. Any reduction impact would not hit immediately, but would eventually be reflected during renewal.

The charts above visualize this difference in resiliency between consumption and subscription models during the current downturn, demonstrating the higher sensitivity of consumption models to changes in end-customer demand. Such changes in sentiment can oftentimes cascade into subsequent periods in a more pronounced manner for consumption companies versus a less extreme pattern experienced by subscription companies.

II. Reduced visibility when predicting consumption patterns

Compared to subscription models, consumption models allow for more flexibility so that resources can be spun up or down dynamically based on customer needs. However, one of the resulting implications is that it is harder to predict consumption revenue since this is tied to usage that can be inherently volatile.

In particular, it can be challenging for leaders of consumption companies to determine the best leading indicator for future usage behavior. Traditional forward-looking GAAP metrics such as billings or remaining performance obligations (RPO) tend to be less useful for consumption companies since several of these companies bill in arrears or have low levels of RPO coverage (see chart above). Many consumption companies leverage net dollar retention for signals about future patterns (an example from Snowflake below) but this is a non-GAAP metric and not all software companies disclose or calculate this metric in a standardized manner.

As a result, management teams of consumption companies sometimes struggle to provide accurate forecasts or guide to the right set of expectations. As Snowflake’s CFO Mike Scarpelli mentioned in last week’s earnings call:

“Before turning to guidance, I would like to discuss the recent trends we've been observing. As I mentioned, we have seen slower-than-expected revenue growth since Easter. Contrary to last quarter, the majority of this underperformance is driven by older customers. Although we expect this to reverse, we're flowing these patterns through to the full year due to our lack of predictability and visibility.”

Goldman Sachs has noted that consumption-model software companies have made more significant downward estimate revisions to CY23 revenue since initiating guidance compared to their subscription model peers. For instance, from 3Q22 to 4Q22, MongoDB’s CY23 estimates came down -4%, Datadog -6%, and Snowflake -3%, vs. -1% for Goldman’s broader coverage. Yet, in reflecting on CY22 top-line performance, Goldman notes that despite more volatility in consumption patterns, consumption companies outperformed consensus somewhat meaningfully (see chart below). This perhaps underscores the difficulties of accounting for both short-term and long-term usage volatility, leading management teams of consumption companies to skew more conservative in their guidance.

III. Valuation implications for consumption models

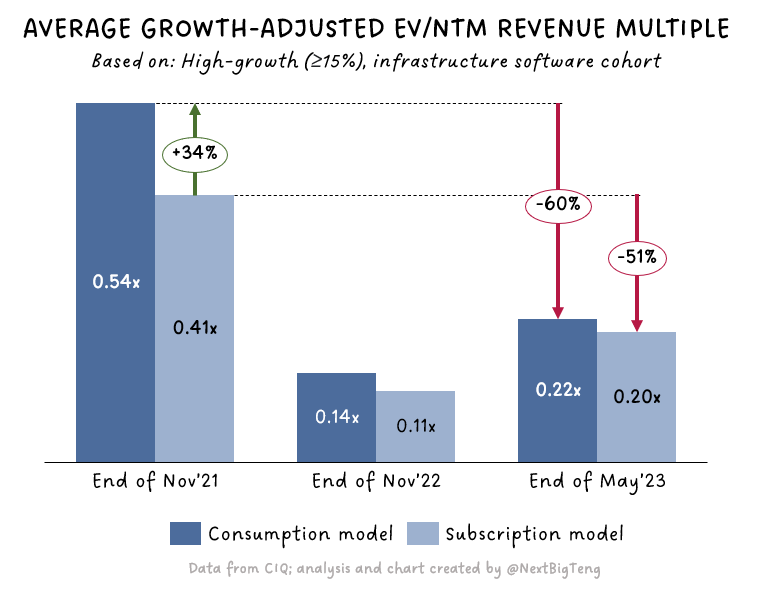

Given the higher reactivity of consumption models to systematic risk, I hypothesized that there should be some degree of cyclicality associated with how investors value this model in different macro environments. The data showed this to be true to a certain extent. At the height of bull-market sentiment in November 2021, consumption companies did indeed command a meaningful premium compared to their subscription peers on a growth-adjusted basis (see an infrastructure-specific case study below). As highlighted in Section I, this premium is unsurprising since consumption companies should structurally be able to capture growth tailwinds more effectively during boom times.

I had expected a complete reversal of this trend following the SaaSacre in 1Q22, since, assuming all else equal, subscription companies should structurally exhibit more resilience and predictability during recessions, which may be traits that investors over-index to during uncertain times. However, data from the current period shows that while the previous expansionary-period premium had evaporated, consumption companies are not necessarily being disproportionately discounted today compared to subscription companies. Consumption companies did experience a greater pullback in valuations compared to the subscription model cohort as investor sentiment changed… but this corrected their valuations to a comparable trading level to their subscription peers, not behind them (chart above).

This finding could perhaps be a result of other factors at play that are not fully-captured by pricing models alone, such as profitability considerations and operational execution elements. One could also argue that this “same floor, higher ceiling” phenomenon reveals that investors understand the inherent trade-offs with this model, and are perhaps more long-term in their view, recognizing the fundamental advantages of consumption-based pricing when recovery ensues. As discussed in Section I, it is logical to deduce that consumption companies are faster to bounce back once conditions rebound since subscription models will exhibit some lag to the market, and historical precedent has shown this to be the case:

As with any business model, the consumption model is not perfect. This dynamic model can serve as a powerful accelerant under the right conditions. But it can also morph into a double-edged sword given its higher propensity to be affected by external conditions, and certainly warrants closer attention from operators and investors alike around its nuances during changing market environments.

It doesn't need to be an either/or situation. Use a base fee with a certain amount of included usage, then charge for overage usage. At renewal time, adjust the base fee up or down depending on actual usage at that time - with or without headroom for growth.

Very interesting breakdown of the business model. Subscription models protect / reduce downside but also limit upside (if no overages); however, depending on the customer base this might make sense. For instance SMB customers are wary of not ending up with large bills that are over budget due to going over their tier.

Recently wrote about how every company business model is converging to X-as-a-Service. It's definitely an interesting time for software.

https://brandanatomy101.substack.com/p/is-every-company-becoming-a-software