Growth-stage startup valuations: Guiding principles for comps selection

Even 'sophisticated' investors have made the costly mistake of picking wrong relative valuation comps. To avoid missteps, here is a proposed first principles framework for comparable company analysis.

Valuing an early stage startup can sometimes seem more of an art than a science since textbook valuation techniques may not fully capture fundamental value, especially if a company is still pre-revenue. Some common methods employed by investors at this stage include frameworks such as ownership requirements, dilution benchmarks, or expected returns/probabilistic analysis. You can check out how some of my colleagues at Bessemer conduct early-stage outcomes analyses in these published investment memos. My colleague Talia Goldberg has even open-sourced a scenario analysis template for founders to leverage.

In the growth stage (later startup stages and post-IPO) where I spend most of my time, private and public market investors commonly apply valuation techniques involving:

Absolute value models (such as discounted cash flow models, dividend discount model, sum of the parts) that attempt to capture intrinsic value, or

Relative value methods (such as PEG ratio, price-to-book ratio, EV/NTM revenue multiple) to assess the value of a company using a comparative approach to peers (comps) or market benchmarks. Below is an example of how a standard comp sheet might be set up for application software:

While these absolute and relative valuation methods may seem more traditional and formulaic compared to early-stage valuation techniques, there is still meaningful room for subjectivity around assumptions. For instance,

wrote an insightful piece on the inherent flaws of the DCF model. Rick Zullo of Equal Ventures wrote recently about how VCs should stop leveraging relative valuation models like revenue multiples, and revert back to the DCF:

The inconvenient truth is that VCs over-tinkering with valuation spreadsheets for startups is oftentimes an exercise in false precision since underlying assumptions will carry a certain margin of error. No method is perfect; there are pros and cons for each technique. It is perhaps more useful for different absolute and relative methods to be considered in tandem to reduce error and triangulate to an acceptable valuation range.

“Apples to Apples” or “Apples to Oranges”?

When I was in business school several years ago, one of the most heated discussions I witnessed was during a case debate on whether WeWork should be valued more as a tech company or more as a commercial real-estate company when using relative multiples. With the benefit of hindsight, we all know how this story ends, but at the time, you would be surprised at how disparate views were on this company. On this theme, I’ve also written previously about how many 2021 IPO investors had mis-categorized non-tech companies as “tech”, leading them to value companies incorrectly by paying a multiple closer to premium tech comps instead of those of the proper peer set such as apparel, consumer goods, insurance, finance, or retail:

Even within the software universe, comparable company analysis can sometimes be tricky, with a meaningful delta between valuation multiple benchmarks for different groups:

Will an AI software platform focused on legal use cases trade more like AI comps or legal tech?

Is a B2B SaaS player with meaningful payments revenue going to trade more like enterprise software or fintech?

Does a vertical SaaS customer communication platform resemble vertical software counterparts or horizonal CPaaS players?

Choosing the right set of comps is not just relevant to the selection of multiples when using a relative valuation method. It can also be employed in absolute valuation methods such as to determine asset beta when calculating the weighted average cost of capital component of a DCF model. Getting comps wrong can lead to incorrect input assumptions which could ultimately end up being a very pricey misstep when multiple compression occurs. As alluded to earlier, even ‘sophisticated’ investors have made these mispricing mistakes.

I recently led a session with my Frontier Tech colleagues on considerations for comps analysis. They are primarily investing in futuristic technologies such as spacecraft and novel food proteins (check out their State of Deep Tech Report and curation of The World's Top 100 Private Deep Tech Companies published this week), so comps selection is not as straightforward in their world given many of their companies do not have truly comparable “apples to apples” peer archetypes. This led us to drill down on a first principles framework for comps selection which I’ll dig into below:

Which metric captures the economics of the business?

Is the peer set truly comparable?

Are the comps fairly valued?

I. Which metric captures the economics of the business?

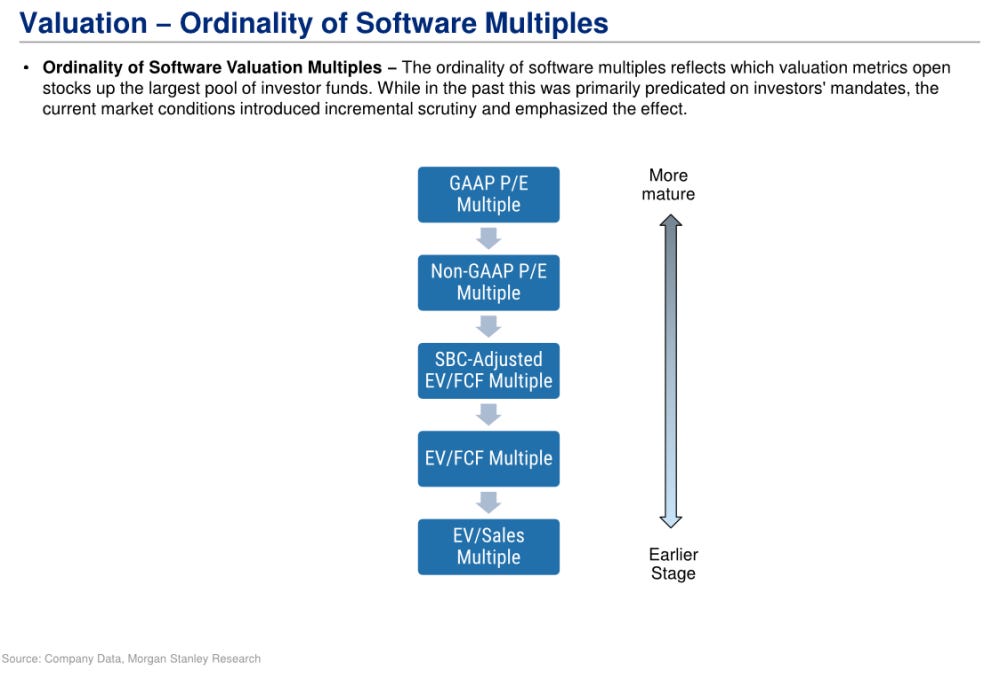

This is a first order question since one needs to first determine what financial metric a company in a particular industry or category is being valued on by investors, before being able to select which “unit” of multiple to use. This unit might also be dynamic based on timing of sentiment or geography. Most later-stage software companies receive support for valuation based on a revenue multiple, such as EV/NTM Revenue, since they are still on the path to maturity and are not yet fully profitable. However this is not always the case based on the company’s profile:

Some SaaS companies with meaningful payments revenue could evolve to be valued more like a fintech company (e.g. based on gross profit or EBITDA). My colleagues on Bessemer’s healthcare team have also written about a nuanced valuation lens for digital health companies and how tech-enabled services companies had been valued like software businesses on EV/ Revenue multiples during peak market exuberance, when they really should have been valued based on gross-profit rather than a pure topline unit:

II. Is the peer set truly comparable?

In reality, there are few truly comparable “apples to apples” companies. But as a guiding principle to answer this question, I would advocate for picking comps specifically based on the most key systematic risk considerations. This is because in theory, idiosyncratic risk (e.g. firm-specific) can be diversified away while systematic risk (e.g. inherent to the market) cannot.

Examples of systematic considerations could include business model, category impacts, market growth prospects, and value drivers. For instance, the performance of a vertical SaaS company selling to restaurants and reliant on consumer dining behavior is perhaps more closely coupled with the same consumer-spending and retail trends that impact commerce companies, rather than other factors that involve the wider vertical SaaS cohort. The chart above visualizes another example of this comps nuance for subsectors within particular slices of the software stack.

III. Are the comps fairly valued?

As seen in the chart below, a short term view can distort multiples if they are picked at a moment in time, so it is important to take a more long-term perspective of the anticipated exit environment. Several investors fell into this trap during the peak hype of recent years, pegging private entry multiples to current multiples in the public markets and believing that a low interest rate exit environment would persist for years to come, causing them to “overpay” for private assets.

Today, within the cloud world, the situation is reversed from previous bull-market years since we’re currently in a rising interest rate environment. Interest rates govern multiples, and as seen in the chart below, current multiples (in absolute terms) are below long-term averages since we’re in a higher rate environment compared to previous years. As I’ve written previously, your conviction on the fair value level of multiples will likely be based on your view of where interest rates stabilize in the coming years. Overall, it is prudent to form a view of where you believe rates will stabilize during the asset hold period/at exit in order to triangulate your willingness to pay.

Additionally, some industries such as energy and chemicals encumber cyclical elements. Even within the software and cloud world, particular business models may sometimes exhibit slight cyclical nuance.

also highlighted a second order question today that your expectations on future growth will also impact your view on how fairly valued comps are on a growth-adjusted basis:

Ultimately, as highlighted in the introduction, relative valuation methods such as comparable company analysis are not perfect and should be used in conjunction with other methods to triangulate valuation range. What are your guiding principles for picking comps? Leave a comment below!