When free-cash-flow margins don't tell the full story

Some thoughts on why investors shouldn't take reported FCF at face value

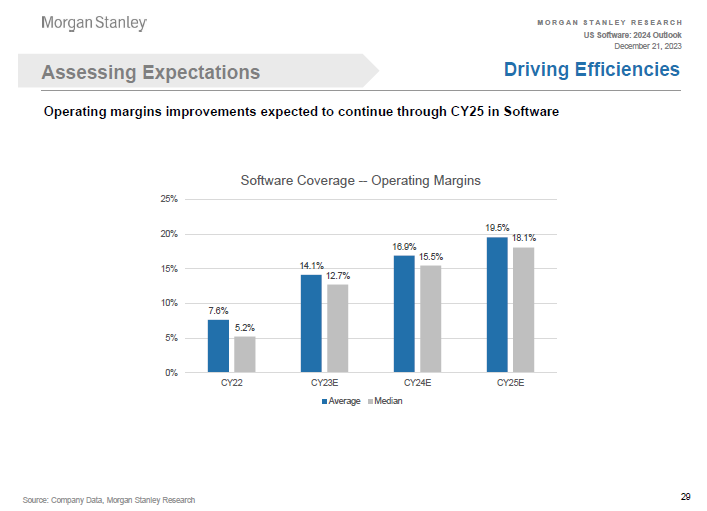

Efficiency was undoubtedly the zeitgeist of 2023. VCs (myself included) harped on this mantra and cloud leaders took heed to steer their companies toward profitable growth instead of growth at all costs. This pivot was fast and effective; software companies are now driving record-levels of free-cash-flow, with forward margin estimates over double the 10-year average:

Such efforts to drive profitability are not going unnoticed by investors, driving higher multiples for more efficient companies (chart below). But as previously unprofitable companies push toward breakeven or even turn FCF+, it is starting to become clear that not every percentage point improvement in FCF margin is rewarded equally in terms of valuation premium.

A “headline” FCF margin number does not tell the full profitability story of a business. Just as quality of growth matters (e.g. organic vs. inorganic), the underlying reasons behind FCF improvement matter. Within the software universe, investor scrutiny leads to cases where companies with seemingly high FCF margins do not get full valuation credit for their performance and trade lower than peers with seemingly comparable fundamentals.

A quick refresher: FCF is commonly calculated as (Earnings before interest and tax * (1 – tax rate)) + Depreciation & Amortization - Change in Net Working Capital - Capital Expenditures + Non-Cash Charges

My colleagues and I have written previously about tactics to increase gross and operating margins in order to drive higher FCF levels. I commend public cloud companies for focusing on operating leverage and operating margin improvements (chart below) as I consider these to be the highest quality means of driving FCF, since such changes are structural and tend to be more long-lasting.

Non-structural drivers can also be leveraged to attain FCF improvement on an absolute basis, but I often find these to be less permanent (and sometimes even potentially misleading). Some examples from recent earnings reports:

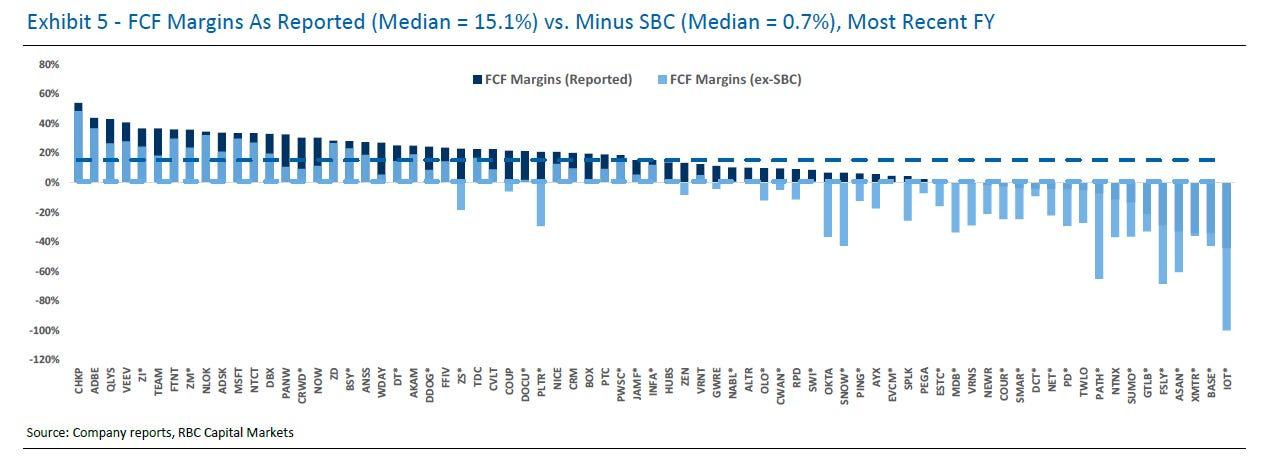

I. Stock-based compensation (SBC): I’ve written a series of articles about SBC overhang in the software industry, highlighting how SBC can serve to “flatter” FCF margins and mask underlying profitability profile since it is added back as a non-cash charge. This is especially problematic in situations where FCF margins look strong but SBC is more than 100% of FCF:

II. Changes in net working capital: Net working capital refers to the difference between a company’s current assets (such as cash, accounts receivable, and inventories) and its current liabilities (such as accounts payable and accrued expenses). After the tide turned in 2022, many companies exercised better discipline in managing net working capital, which served to boost FCF. Examples of optimizing the ratio of receivables to payables include extending vendor payments, initiating payment plans, or focusing on collections. A case study from Samsara:

“I mean I think the biggest driver is obviously the working capital dynamics. You go back a year ago, I think free cash flow was like 18 percentage points below operating margin, and that was really driven by the challenges in the global supply chain. And now I think in this quarter, we were 8 percentage points better on free cash flow than operating margin. So it's clearly flipped back the other way. And the biggest driver in the difference is the working capital optimization, and we had a really strong collections quarter, and we continue to see improvements in supply chain and hardware availability. I expect these things to move relatively in line with each other.” - Dominic Phillips (CFO of Samsara) during Q1 2024 Earnings Call

III. Deferred revenue and upfront billing: FCF can sometimes be temporarily elevated due to upfront billing, resulting in a large balance of long-term deferred revenue where a significant cash inflow happens before services are delivered. Such unearned revenue is recorded as a liability on the balance sheet. Interestingly, RBC found that cybersecurity vendors seem to have above-average exposure on this vector:

Changes to shorter payment cycles could result in significant impact to FCF. Autodesk is an interesting example that demonstrated this point when the company moved from upfront to annual billings for multiyear contracts:

“The transition to annual billings means that about $200 million of free cash flow in Q1 fiscal 2024 that came from multiyear contracts built upfront will not recur in fiscal 2025. This will reduce reported free cash flow growth in fiscal 2025. And make underlying comparisons between the two years harder.”- Debbie Clifford (CFO of Autodesk) during Q3 2024 Earnings Call

IV. CapEx: One would expect this lever to be uncontroversial in the SaaS universe as cloud businesses should in theory have less capex needs compared to other types of businesses such as those in manufacturing. However, I’ve soon come to realize that this lever can be tricky as well. Some examples:

Capex for software companies tend to involve items like new office construction or server-build outs (especially for infrastructure layer companies). It is key to truly understand if these are one-time events or end up being recurring, especially in the case of particular data center costs for AI focused companies.

Some companies have a practice of capitalizing and then amortizing sales commissions over a contract period which adds complexity if the assumed amortization period does not closely match the length of contracts in reality. Some short sellers criticize this practice as an “accounting distortion” used to overstate margins.

Understanding the financing of capex is also important, such as in Amazon’s case where leases are used to finance parts of capex, leading to a highly unusual situation where Amazon reports on three different definitions of FCF.

Not perfect but still important

As all of this discussion has shown, non-GAAP financial measures like FCF are certainly not perfect (just read Warren Buffet’s criticisms of EBITDA). There are often shortcomings to be considered and industry specific nuances that need to be layered on.

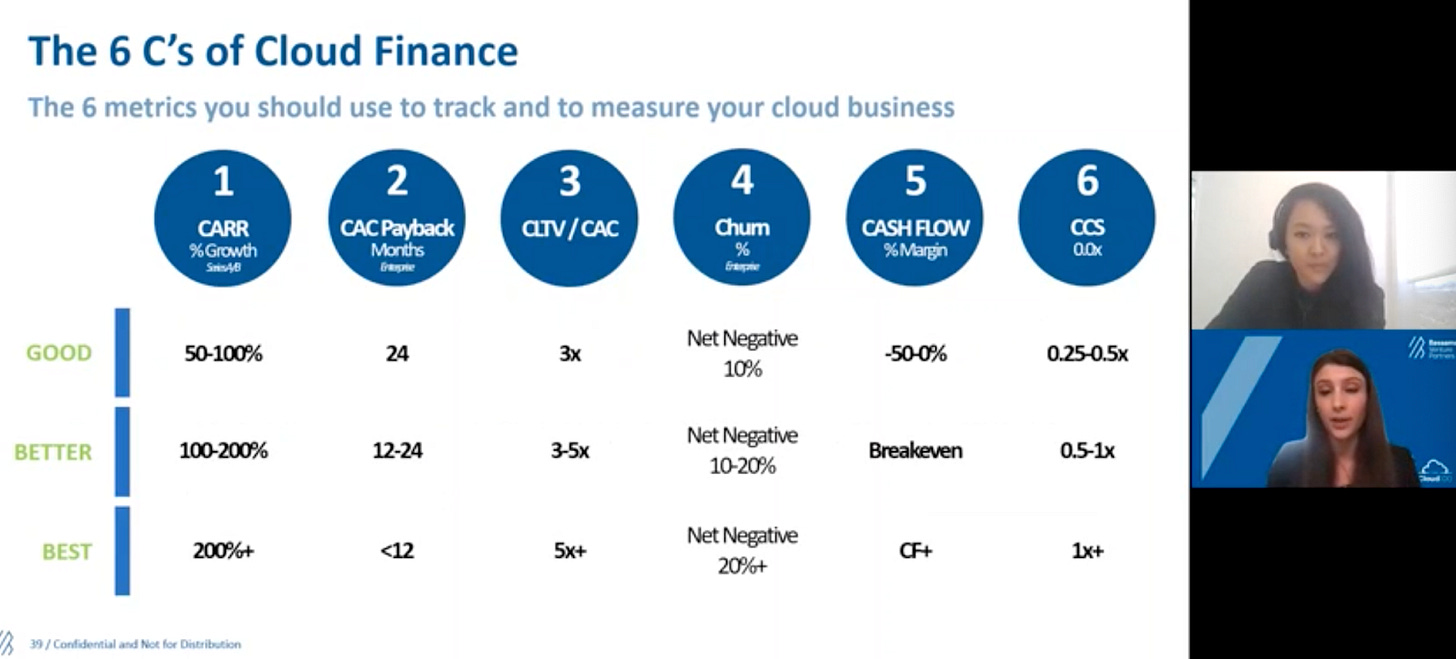

Still, I view FCF as an important KPI for software businesses— cash burn limits runway for businesses that are consuming capital, and for businesses that are cash-generative, FCF represents re-investable dollars that funneled back into the business or returned to shareholders. This is why FCF is one of the key cloud metrics I track closely as a venture investor (visual above). However, it is crucial for investors to prudently diligence the underlying drivers of FCF margin in order to truly assess a cloud business’ underlying long-term profitability profile.

Great perspective and writing!

also watch out for FCF _per share_.