Eschewing IPOs: What happens when SaaS companies stay private for longer

The median age at IPO for US companies is now over 10 years. Staying private has its advantages, but what are corresponding externalities when companies remain private for extended periods of time?

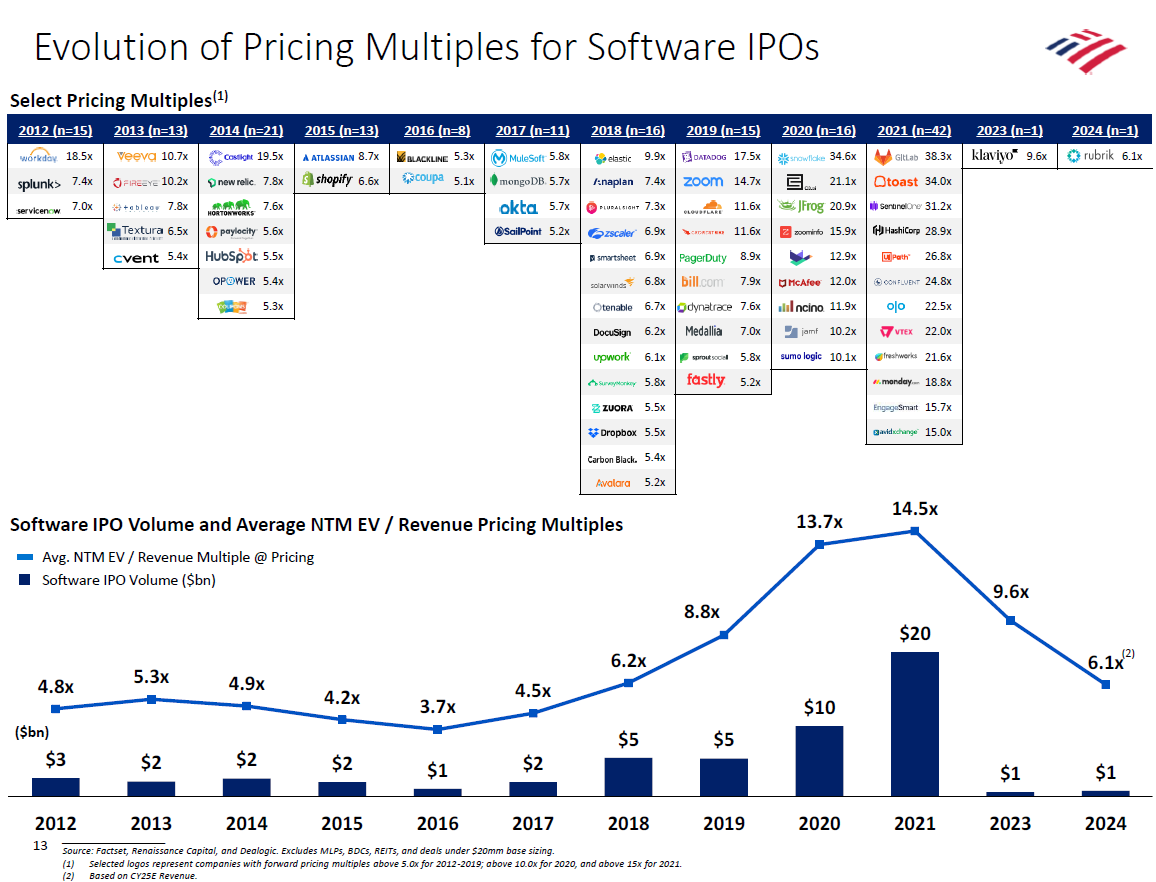

Almost a year has passed since I wrote about Klaviyo’s IPO which ended an almost two-year drought of SaaS IPOs. Sadly, Klaviyo’s foray into the public markets did not spark an inflection in the chilly SaaS IPO environment. Rubrik’s IPO earlier this year has been the only other major SaaS IPO since:

General market sentiment within the SaaS industry has been muted throughout 2024, but over the past few weeks, chatter has re-emerged around the return of SaaS IPOs following OneStream’s S-1 filing.

For the few SaaS companies that have made it to the IPO milestone recently, a maturity trend is emerging: Klaviyo, Rubrik, and OneStream, were all over a decade old since founding (in OneStream’s case close to 14 years old) before going public. In fact, the median age at IPO for US companies is now ~11 years versus ~8 years during the 1980-2000 period:

While staying private has advantages, this trend has externalities for many in the ecosystem. For instance:

For employees, especially early joiners, startups staying private for longer could result in a longer time till they can experience liquidity. To add more complexity, US tax rules mandate that unexercised employee stock options expire 10 years from date of grant. Providing employees with liquidity has been a hot topic in recent years, with more companies looking to formalize programs or leverage new platforms to address this issue.

For VCs, investors often underwrite investments based on their hurdle of a required internal rate of return (IRR). IRR is a function of both time and multiple of return, so as this trend of companies remaining private for longer continues, standard underwriting assumptions will need to evolve as well. More acutely, similar to Point 1 above, liquidity risk and pressure around distribution periods for limited partners (LPs) have been key points of discussion as the timeline for VC funds holding on to private assets becomes increasingly extended (chart below). Recently, funds such as Sequoia have come up with creative ways to offer liquidity and returns to LPs for long-in-the-tooth assets.

For public market or retail investors, some purport that companies staying private for longer could mean that there is less value creation (and consequently value accretion) occurring post-IPO:

This trend of companies staying private for longer has sparked a rallying cry for founders to re-examine previously held beliefs around what milestones (such as scale) need to be achieved before a company should go public. Others also point out that “the dearth of software IPOs is due to mismatched expectations, NOT a ‘shuttered IPO market’” as many private high-growth software companies can IPO but may need to overcome a potential valuation hit initially.

I have written at length about this private-public market valuation disconnect (see chart above for an updated visual of this phenomenon). However, all of this will undoubtedly take time to unravel, so don’t expect a sudden reversal in exit trends any time soon.

No fair using eschew in a headline. :-). Great post, if I have time I'll do one myself that builds on this because I grew up in a Silicon Valley where you could go public in 4-5 years and off $30M in revenue. And I think that was overall better for a number of reasons, mostly related to employee liquidity, ability to change jobs, ability of the individual investor to buy shares in companies early (e.g., Oracle at $100M in revenues) and even for institutions who could buy shares in early-growth companies without 2+20 fee loads.