Schrödinger’s Startup Paradox: Locked inside the last round valuation box

Startups & VC funds have been caught in a limbo period where private valuation marks seem disconnected from public comps, but this is starting to unravel. Is the great recalibration finally upon us?

Schrödinger’s paradox is a famous thought experiment of quantum superposition where a hypothetical cat is locked in a box with a radioactive substance controlling a vial of poison. As the substance decays, it triggers release of the poison which will kill the cat. However, since the box is locked, an observer is unable to tell if the radioactive source has decayed, thereby creating a situation where the cat may be considered to be alive AND dead simultaneously. Only by opening the box can one unequivocally know if the cat is alive OR dead.

While the VC industry rarely draws parallels from the world of quantum mechanics, following the SaaSacre in early 2022, startups (especially later-stage ones) have been caught in Schrödinger’s paradox as it relates to private valuations.

Inside Schrödinger’s last round valuation “box”

Venture investors, especially at the growth-stage, often track the performance of comparable public companies and factor these multiples into entry prices for VC deals. Interest rates govern multiples with an inverse relationship. During the ZIRP environment, public comps were elevated and private multiples mirrored this. Then, at the start of 2022, as rate hikes began impacting public comps, net new private fundraising activity quickly saw an inflection as the VC market reacted quickly in terms of reducing the number and size of new unicorns:

However, many startups had raised in the frenzy of 2020-2021 when there was peak investment activity and higher public comps. Unlike public companies, private companies are not marked to market daily. Rather, they report valuations based on the last private fundraising round. Consequently, despite the changed public market valuation environment which would seemingly indicate that the last round price might be underwater, many startups are still holding on to strong valuation marks on paper.

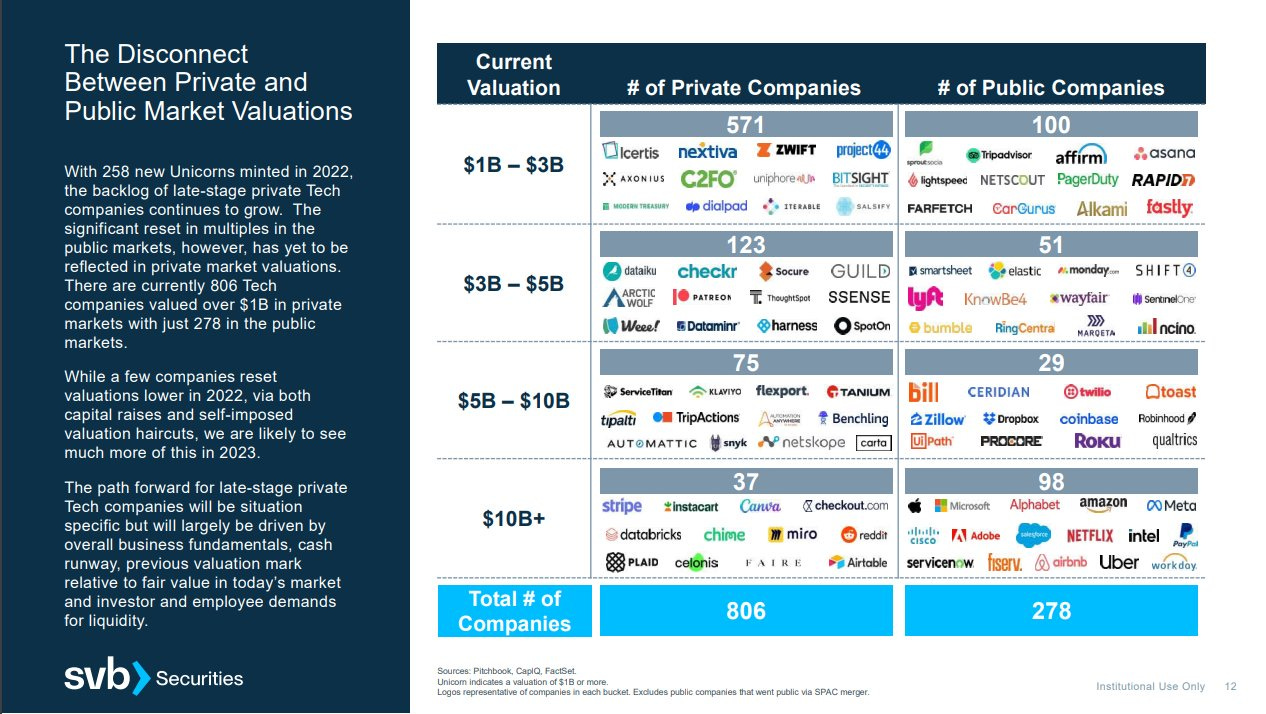

I’ve noted previously that this phenomenon has led to a significant private-public valuation disconnect. In 2022, there were 806 private tech companies valued >$1Bn based on last round price, but only 278 of such tech companies in the public markets (chart below). As another illustration of this point: Morgan Stanley reported that there were 1415 global unicorns in 2022, but only 715 EBITDA-positive companies had IPOed at a valuation >$1bn over the last 5 years.

This paradox also appears in the books of venture capital funds. One of the common metrics that VCs report on for fund performance involves Total Value to Paid In Capital (TVPI). TVPI is an attempt to calculate both realized and unrealized value that a fund has generated for investors relative to the amount of money contributed. Unrealized value is often assessed based on last round marks, resulting in a situation where the book value of a VC’s portfolio looks high on a TVPI-basis, but only in theory since this is unlikely to fully convert into realized distributions (as measured by another metric Distributed to Paid-In Capital) as we enter a new valuation paradigm.

Opening the “box”

As in Schrödinger’s experiment, one can only discern the fate of a startup’s valuation or portfolio’s return when the “box” is opened. There are several ways for this to happen. One common way is when a private company runs out of cash and needs to return to the VC market to raise their next primary round. There was a bit of a lag on this front as startups managed their cash runway more efficiently to avoid a potential reckoning. However, the ecosystem eventually saw a noticeable uptick in downrounds and this percentage is currently above long-term historical averages. Unsurprisingly, given the private-public valuation disconnect, especially amongst the unicorn cohort, the average company raising at a downround currently has a post-money valuation over $1bn, which is at its highest level in recent years:

As I noted last month, a similar trend emerged in secondary markets as well, with Morgan Stanley’s data indicating that the average VC secondary transaction in 2Q23 cleared at 40% below previous primary transaction price levels. Signs are also emerging on the M&A front, with a recent example being Atlassian’s acquisition of Loom at a valuation ~35% less than the former unicorn’s last round price.

The private markets also responded from a multiples perspective. My colleagues and I observed from 2023’s Cloud 100 cohort (the definitive list of the top 100 private cloud companies globally) that the average Cloud 100 valuation multiple had decreased for a second year in a row from 34x in 2021, to 30x in 2022, to 26x in 2023 (chart below). While trending in the expected direction, this decline is still smaller in magnitude than what has been observed in the public markets, where the average BVP Cloud Index forward trading multiple has come down ~65% since the start of 2022 and down ~78% from 2021’s maxima.

Another way to open the “box” is to enter the public market. This is a more visible litmus test since, unlike in a private or M&A setting, companies that IPO are required to publicly disclose financial information, allowing investors to benchmark business fundamentals against valuations. As I previously discussed, all eyes were centered on the IPOs of ARM, Instacart, and Klaviyo last month, since these three bell-weather IPOs would provide the first signals around public market demand and valuation sentiment for venture-backed tech companies after 2022’s pullback.

Klaviyo’s performance was of particularly high interest to those in the SaaS startup ecosystem since its IPO pricing would set a clear yardstick for what public markets perceived a cloud market leader to be worth in the current paradigm. For a business with strong fundamentals (solid scale at $585MM, attractive growth of 57% YoY, profitability of 8% FCF margin, and an impressive 65% efficiency score), Klaviyo priced at ~10x forward at the time of IPO. This accorded the company with a public market cap somewhat in-line with its last reported private valuation:

The average forward trading multiple of the BVP Cloud Index is currently ~5.5x, reinforcing how the public market is indeed rewarding Klaviyo with a significant premium for its outstanding business performance. However, in the context of growth-stage private cloud companies being priced at an average of 26x current in 2023, Klaviyo’s precedent seemed more like a sobering dose of reality rather than a celebratory affair.

Will there be full convergence?

Now that the recent IPO flag-bearers have very tangibly opened Schrödinger’s valuation “box” and set a clear bar for other growth-stage cloud companies, will we finally see the sweeping recalibration of private valuations that so many in the industry had been prophesizing over the last year?

Just within the last few weeks, we have seen some early signs in this regard. According to Forge Global, median pricing for private secondaries of VC-backed startups experienced a meaningful jump from a 50% discount in August 2023 to a 63% discount in September 2023 (chart below). Surprisingly, the top decile and top quartile companies were the most impacted — the 90th percentile saw a huge swing from a 42% premium in August to a 20% discount in September, and the 75th percentile moved from a 22% discount in August to a 48% discount in September. This recent trend is even more shocking given the context that the 90th percentile cohort had been relatively immune from recalibration implications over the past 20 months, and had actually been trading on average at a premium to last round price (when all other percentiles were at a discount) until September.

Additionally, Forge Global noted that the bid-ask spread between buyers and sellers has been coming down over the past year (chart below). That said, the current delta is somewhat in-line with the long-term median of 14% and has held steady at these levels over the past few months. This is somewhat surprising since one could have logically expected the spread to have fallen below the long-term historical trend by now given the multiple signals highlighted in the preceding section.

Ultimately, unraveling the private-public valuation paradox may not be so straightforward. There are many drivers that may explain why a valuation disconnect in the private and public markets could be expected to persist or take longer than expected to converge. One theme that my team has been discussing recently to explain the expectations gap is the record amount of dry powder (i.e. VC capital to be deployed) in the ecosystem:

Several funds could be tied to a specific timeline or mandate and will need to deploy within a defined period or with particular assets over the near term. Every fund also has a different return threshold or may have lowered hurdles after the pullback, injecting more volatility into the system. All of this could take years to clear before valuations in the private growth-stage system returns to some semblance of historical normalcy.

Great post. Remember that a small part of the paradox at least is explained by the fact that those later-stage private investors were buying preferred stock with small to potentially large preferences that can make the "valuations" non-comparable. That is, just because I spent to $100M to buy 10% of a company with a 2x liquidation preference doesn't mean the company's "worth" $1B pre-money. This problem is, in part, due to the fact that Sand Hill Road loves to multiple the preferred price by the total of common and preferred shares to arrive at these headline valuations. That doesn't explain everything, and I do very much agree this problem exists. But part of it, at least, is not that paradoxical.

Charlie Munger says to buy great businesses at a good price and not to buy good businesses at a great price. The reverse is true when selling equity. Be raising capital in a great business and at a good price and not the other way around.